Diving for Treasure in a Sea of Scientific Literature: Extracting Scientific Information from Free Text Articles

25 Jan 2021 - Aarthi Koripelly, University of Chicago

It has become impossible for researchers to keep up with the more than 2.5 million publications published every year. We explore scalable approaches for automatically extracting relations from scientific papers (e.g., melting point of a polymer). We implement a dependency parser-based relation extraction model to understand relationships without the need for a Named Entity tagger, integrate several word embeddings models and custom tokenization to boost learning performance for scientific text.

The exponential growth of scientific publication is overburdening researchers, who now have to read hundreds of publications just to understand the current state-of-the-art technology. Even with herculean efforts, it is still likely that they will miss important papers or key information included in papers. Crowdsourcing is often suggested as a scalable method for extracting information from publications; however, it is infeasible as most people do not have the necessary expertise to extract information from scientific paper. Scalable and automated methods are required to process papers and to extract important facts, including molecular compounds and the relationships between different compounds such as (aluminum, melting point, 660.3 °C) from the the text:

“The melting point of Aluminum is 660.3 °C.”

Approach

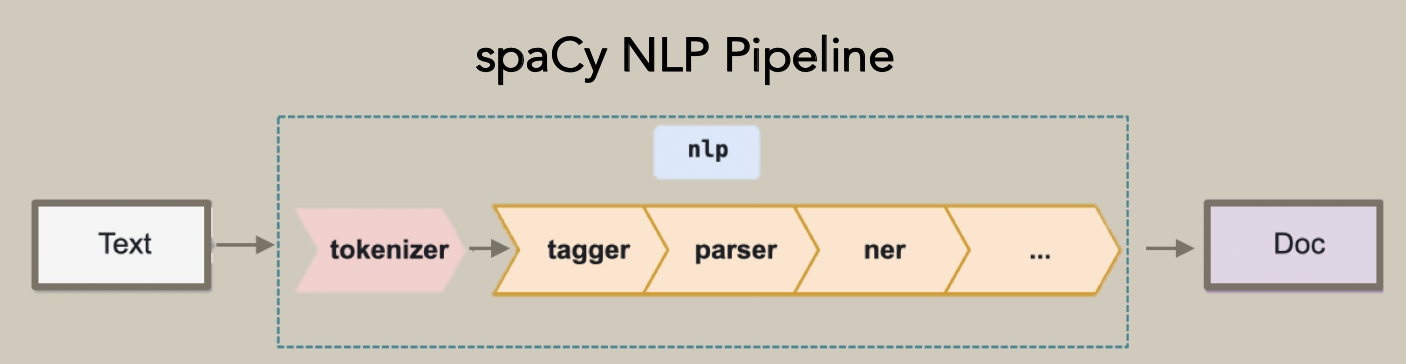

Traditionally, relation extraction consists of five stages: tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, named entity recognition (NER), phrase parsing, and information extraction. We focus here on developing a relation extraction pipeline using a dependency parser rather than using costly NER. A dependency parser analyzes the grammatical structure of a sentence, establishing relationships between “head” words and words that modify those heads. We used a dependency parser, as they are useful for extracting relationships between words using only their parts of speech. We used a dependency parser provided by spaCy and customized it through tokenization and word embeddings.

Figure 1. spaCy NLP Pipeline.

Performance of Model

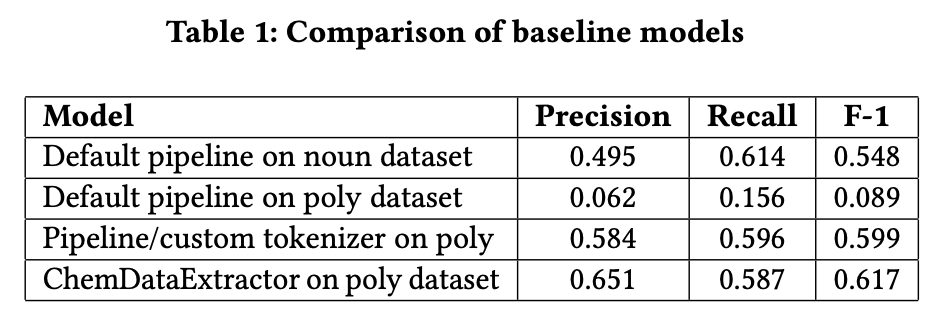

We first explored the accuracy of a dependency parser pipeline using spaCy’s default tokenizer and word embeddings model (‘en_core_web_sm’). We then attempted to apply the same pipeline to the polymer dataset; however, it performed poorly due to the difficulty identifying entities in scientific text (e.g., hyphenated and non-dictionary words). To address this limitation we developed a custom tokenizer that combines words with hyphens, degrees signs, and other symbols necessary for understanding polymer notation. We again used the default word embeddings model (‘en_core_web_sm’). Finally, we compared these methods to the state-of-the-art ChemDataExtractor.

Improving Model

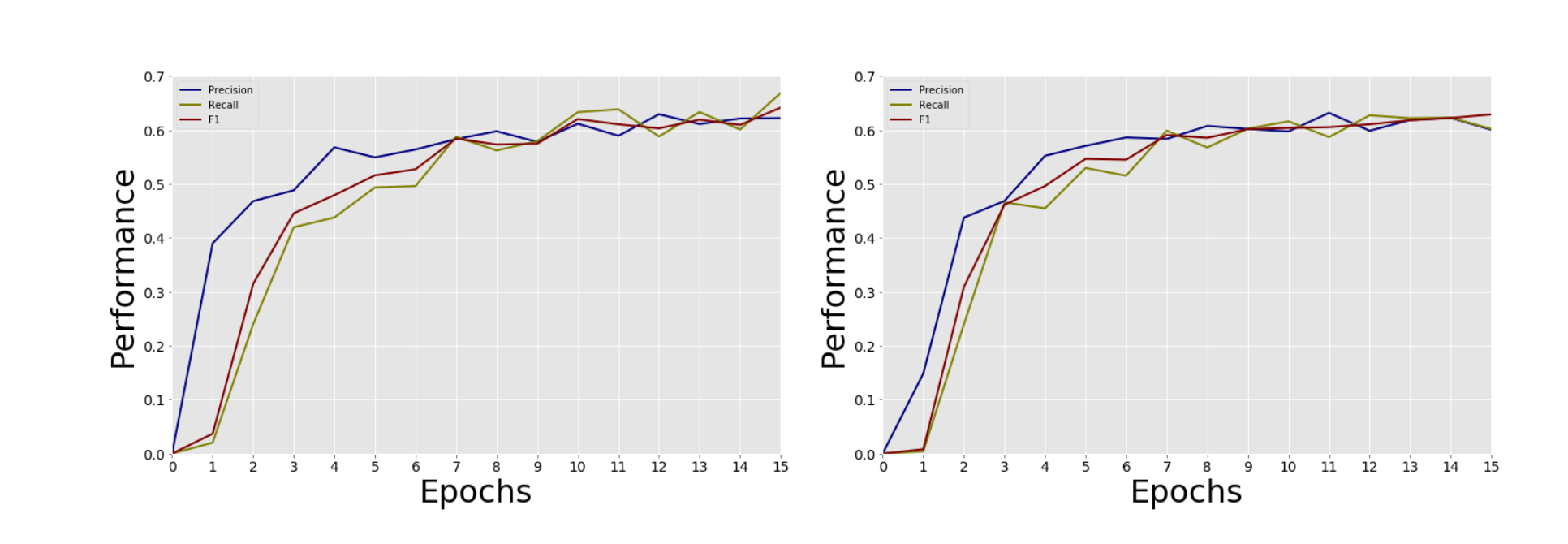

To further improve performance, we trained custom word embeddings using Skip-gram and Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) models from the Gensim library. CBOW determines the semantic and syntactic information of a word based on the context in which the word appears. Skip-gram uses a context window around the center word for which it creates a word embedding vector.

We used k-fold cross validation to evaluate our model. We set k = 5 and took a mean of the evaluation scores to determine the model’s performance. We evaluated our CBOW and Skip-gram models using default hyperparameters. We changed various hyperparameters while training our word embeddings and found that the default CBOW word embeddings gave us the highest F1 score of 0.671.

Figure 2. CBOW vs Skip-gram Training Performance.

Scaling

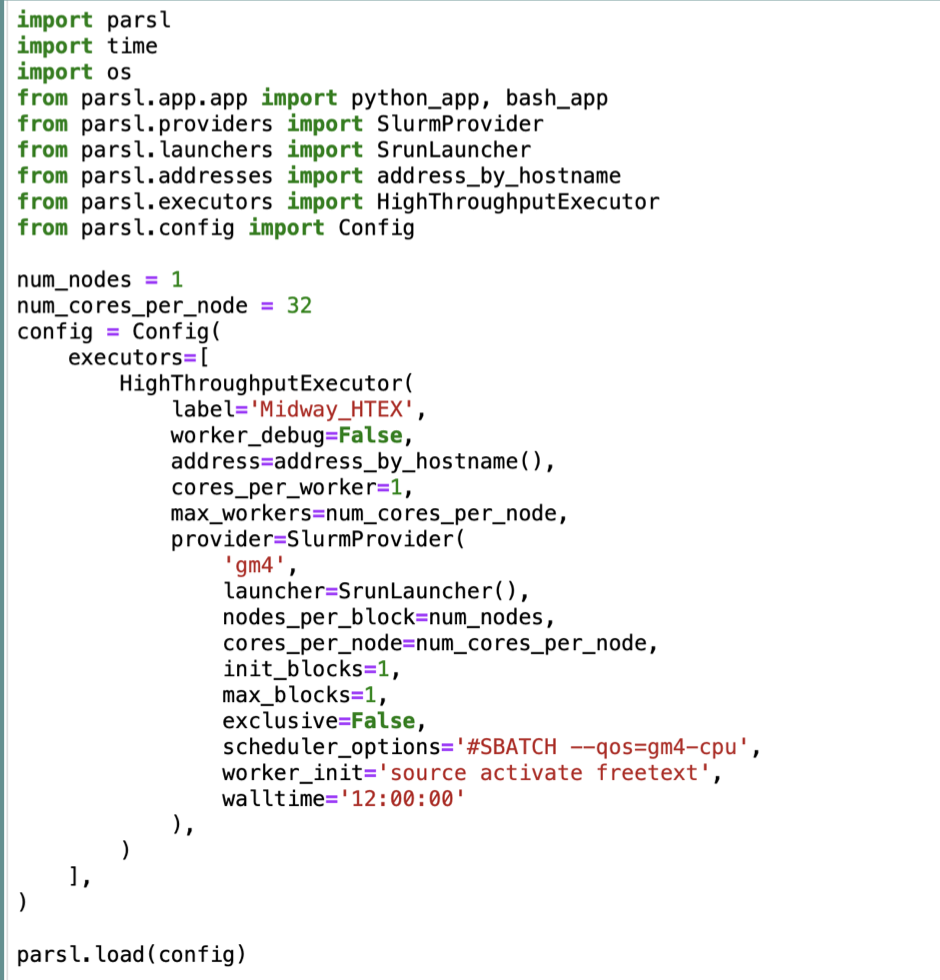

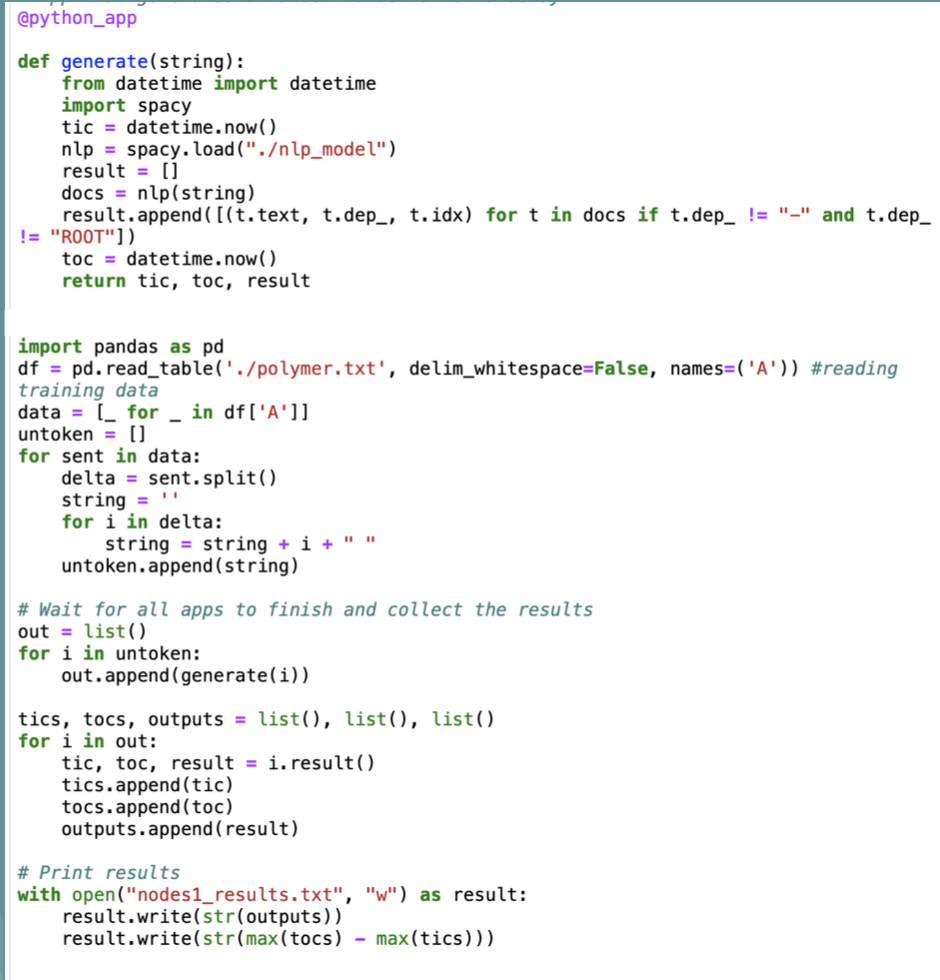

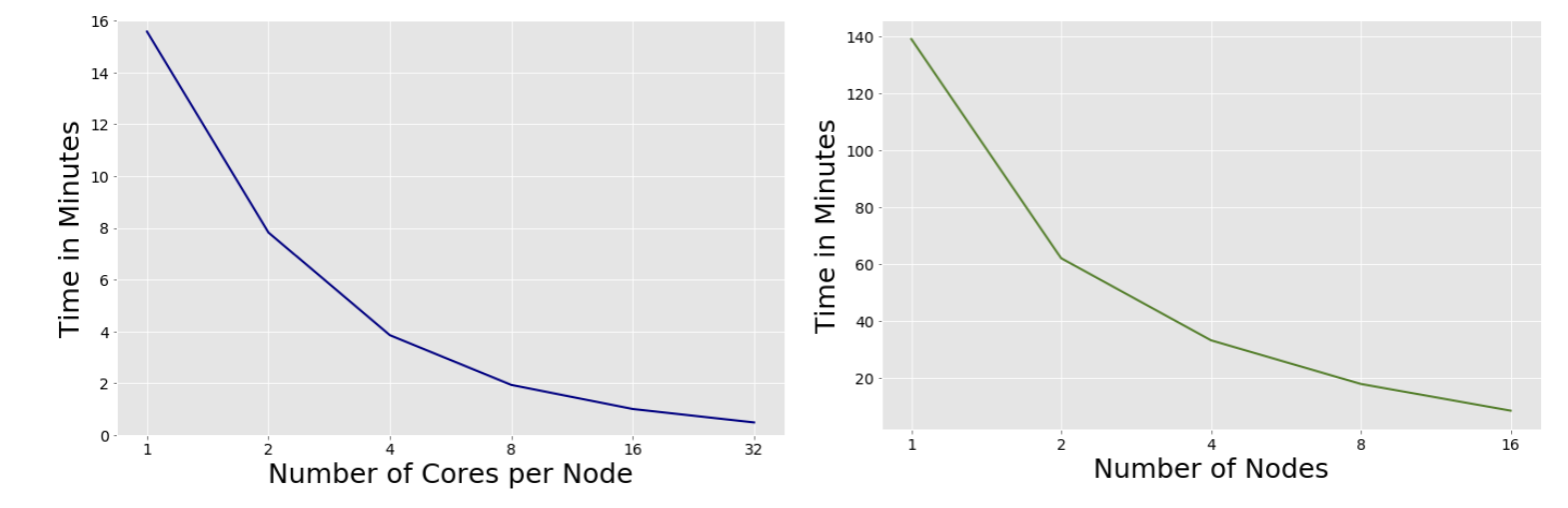

To scale our model, we used Parsl to create parallel programs composed of Python functions and ran our model with a larger dataset on a set number of nodes and cores concurrently. It was easy to augment our existing Python script and then deploy on RCC (the Research Computing Cluster at the University of Chicago). We explored scaling our pipeline on a single node and across many nodes. We used the full Macromolecules dataset of 300,000 sentences and implemented a Python-based program using the Parsl parallel programming library. We executed our pipeline on a campus cluster. The figure below shows our results when increasing the number of cores and number of nodes (with 32 cores per node). For single-node scaling, we were able to reach peak throughput of 103 sentences per second using 32 cores. When scaling across 16 nodes we were able to reach throughput of 590 sentences per second.

Sample Parsl Code

Scaling Cores on 3000 Sentences, Scaling Nodes on 3000 Sentences

Summary

Natural language processors for relation extraction commonly consist of five stages: tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, named entity recognition, phrase parsing, and information extraction. We were able to train and deploy a successful model without named entity recognition. Our model’s best result for identifying polymer names and relations reaches an F1 score of 0.671 - outperforming the 0.617 achieved by ChemDataExtractor, the state-of-the-art domain-specific toolkit available in the field of chemistry. And using Parsl allowed us to easily augment our existing Python script and then deploy it onto RCC for results. And going forward, we hope that structured and scalable data extraction from publications will be able to process vast amounts of data.